Amy Waltz, JD, CIP

Associate Director – Regulatory Affairs, Reliance, Outreach

Indiana University

Abstract: Understanding context is key to understanding the regulations and complying with regulatory requirements. This article explores the historical context and events that shaped the current human subjects protection regulations and how changes in human subjects research and public perception have impacted the proposed revisions to the human subjects protection regulations. The 2017 revisions to the Common Rule (45CFR46) and the impact of these revisions on government funded research are also addressed.

Introduction

Research compliance is one of the few areas within the United States regulatory system that demonstrates a direct correlation between real-life events, public opinion, and changes in regulatory policy. In 2017, the Common Rule, the set of regulations that defines human subject protection in the United States, was revised for the first time in more than twenty-five years, beginning a new regulatory era in research compliance.

It is extremely important for the research community to understand the context behind those regulations and the recent changes. Understanding the historical context helps researchers and institutional review board (IRB) administrators appropriately balance potential administrative burden with ensuring the highest ethical conduct of research. While the Common Rule, and IRBs, are often seen by researchers as simple administrative burden, they are based in a historical context rife with ethical violations, even when the violators meant well.

The research community is in an excellent position right now, being given the revised Common Rule and the regulatory flexibility that it provides, to use the past to define the future of research.

Early examples of human subjects research

Research in the early years of medical experimentation looked very different than it does today. Those who participated in research, unwittingly or not, were not categorized as “human subjects” and specifically protected. Today, the lines between research and clinical care are carefully drawn. Research and clinical care are explained differently to subjects, and logistics, such as billing, is handled separately in many cases. In the early days of medical experimentation, no formal distinction between research and clinical care was made, and human subjects research was not considered a separate scientific discipline as it is today. Instead, research was simply conducted alongside clinical treatment.

For example, the great Sidney Farber created chemotherapy at Boston Children’s Hospital. At that time, there were no treatment options for pediatric cancer patients, who almost always succumbed to their disease. As those who work in rare and difficult diseases today can understand, serving as a treating provider for pediatric cancer patients, knowing there was little to be done, was exceedingly difficult. Dr. Farber and his colleagues developed chemical compounds to try to help children with leukemia. Dr. Farber’s work was methodical, ground breaking, and ultimately defined the treatment of cancer; however, the informed consent document as we know it today did not exist for Dr. Farber’s experiments.

Another example of early human subjects research has captured the interest of Americans in recent years. In 1951, George Gey created the first immortal cell line from cells removed from an African-American woman named Henrietta Lacks, who had been diagnosed with a violent form of cervical cancer. The cancer spread extremely rapidly and she passed away within a few months of diagnosis. Dr. Gey was a researcher at Johns Hopkins University who had been searching for an immortal cell line, or a group of cells that would grow for prolonged periods, which he hoped would allow bench scientists to conduct better research. He had asked colleagues at the University and affiliated hospitals to take an extra swab of cells from cancer patients for testing by Dr. Gey. The cells taken from Henrietta Lacks were collected with that request in mind, and no one thought to obtain consent. At that time, the concept of informed consent for research as we know it simply did not exist yet.

Henrietta Lacks’ immortal cells have changed the face of medical research. Her cells are used throughout the medical and research world; however, neither Henrietta Lacks nor her family consented to the original or ongoing use of her cells. The story became widely known in 2010 when Rebecca Skloot published The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, which became a New York Times bestseller. The book resulted in the first public acknowledgment of the contribution of the Lacks’ family to medical science and sparked a national public discussion about the ethical use of biospecimens for research, including how biospecimens are collected, and the information people should have when their biospecimens are used for medical research. Today, the Lacks family is involved in discussions of how some of Henrietta Lacks’ cells are used. The book changed the way the research world treated the Lacks family. The discussion in the research community about biospecimens has changed the regulatory perspective on research requirements.

The worst-case scenario

These examples took place well before research regulations existed. The first consideration of human subjects as we know it today did not occur until after the global public learned of Nazi experimentation during World War II. Before and during World War II, the Nazis committed terrible atrocities in the name of medical science using prisoners of war, Jews, and children. Nazi doctors conducted systematic investigations designed to test very specific hypotheses. Many of the experiments were focused on the war effort and attempted to create a better soldier or lessen the effects of the body’s reaction to cold, hunger, altitude, and pain. The infamous Nazi doctor, Josef Mengele, conducted genetic research on more than 700 pairs of twins.

The world did not hear about these atrocities until the Allied forces entered Nazi Germany toward the end of the war and found evidence of carefully-documented medical experimentation in concentration camps and Nazi strongholds around Europe. After the war, hundreds of Nazis were tried for war crimes and crimes against humanity, including medical experimentation, at the Nuremburg Trials.

Like most legal trials, the judgments rendered at the Nuremberg Trials, and the rationale for those judgments, were documented in the judges’ opinions about the cases. The Nuremberg judges who oversaw the medical experimentation cases thought carefully about the ethics of medical research and how medical research should be conducted. They discussed it extensively in their opinions. The judges eventually wrote the first ethical doctrine for conducting medical research, which became known as the Nuremburg Code. The document is often considered the basis for other ethical doctrines world-wide.

The worst-case scenario here at home

After the Nuremberg Code, unethical research practices were a topic of global debate. Unfortunately, there were examples of ethical violations in medical research here in the United States as well. The Tuskegee syphilis studies brought ethical issues in research with human subjects to the forefront of the public eye. These studies were conducted from the 1930sthrough the 1970s, and they were funded by the United States Public Health Service. The Tuskegee syphilis studies were designed to study the natural progression of untreated syphilis over time. When the research began, syphilis was prevalent in African-American men, especially those in poverty, so study doctors focused on that population, offering recruitment incentives which would be especially attractive to the target participants: free medical care, meals, and burial insurance. Given the participants’ need for these things, many now consider those incentives to be unduly influential.

Undue influence was not the only ethical issue in the Tuskegee syphilis studies. Conduct of the study led to a lack of informed consent and failure to mitigate further risk to participants. For example, when the researchers began having trouble recruiting participants, they simply stopped telling potential subjects that they were studying syphilis. Many of the participants never knew that they had syphilis and were never told, despite participating in the syphilis studies for years. Furthermore, study doctors never offered participants a treatment for their disease, despite the fact that a viable treatment became available in the 1940s, while the studies were ongoing.

It is difficult to imagine research being conducted in this way under the current regulatory environment. Subsequent regulatory oversight of human subjects research in the United States focused on avoiding and mitigating the types of issues demonstrated by the Tuskegee syphilis studies.

Development of the regulations

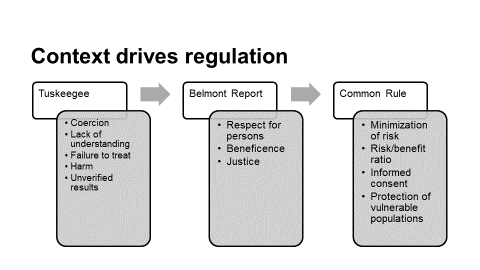

This historical context drove the development of the regulations in the United States (Table 1). The major ethical violations that occurred in the Tuskegee syphilis studies – coercion, lack of informed consent or understanding, failure to treat, and harming research participants, led regulators to directly address such issues in the Belmont Report and the subsequent regulations.

In the mid-1970s, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research set out to develop a set of regulations to ensure that unethical conduct of research no longer happened. After years of work, the Commission developed an ethical guideline, the Belmont Report, which describes the guiding principles for ethical conduct of research in the United States. The Belmont Report outlined three main tenants: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice.

- Respect for persons is the concept of autonomy of research participants, and it requires informed consent to participate in research, as well as a clear understanding that participation in research is voluntary. This tenet also requires protection of persons with diminished autonomy, who may not be able to consent for themselves.

- Beneficence embodies the medical tenet to “do no harm,” and it requires that research be conducted in a way that maximizes benefits and minimizes harm to research participants.

- Justice requires equitable recruitment practices in research so that the benefits and burdens of research are distributed fairly, and those who will benefit from research are those who participate on the research.

The Common Rule

The three tenets of the Belmont Report became the basis of today’s Common Rule. The Common Rule is the set of regulations that requires independent review of research by an IRB to ensure that the research has a sound design and requires additional safeguards for vulnerable populations. The Common Rule has been accepted by the US Department of Health and Human Services and fifteen other Federal departments and agencies that apply to government-funded research. The IRB, under the Common Rule, must determine that:

- Risks are minimized.

- Risks to subjects are reasonable in relation to the anticipated benefits.

- Selection of subjects is equitable.

- Informed consent will be obtained from participants, and that potential participants understand the research and that their participation is voluntary, unless informed consent is waived when specific criteria are met.

- Informed consent will be documented (unless waived).

- The research plan includes adequate provision to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants.

- If subjects are vulnerable to coercion or undue influence, additional safeguards have been included.

The ethical violations in the early years of medical research led to the Belmont Report, which led to today’s Common Rule – a direct correlation from real-life events and public opinion to changes in regulatory policy that continues today.

Today’s research environment

Since publication of the Common Rule in 1991, the research environment has changed dramatically. New technologies such as digital records, electronic medical records, the human genome project, mobile technology, and big data, among others, have changed the way that research is conducted. Research design has changed. Today, researchers encourage keeping data for possible use in future research. Research repositories, precision medicine programs based in research, and translational research are important initiatives. Comparative effectiveness research has changed thinking about informed consent. Today’s research environment includes concerns about privacy and public engagement in research. For example, when the Common Rule was first published, the Health Insurance and Portability and Accountability Act did not exist. Greater visibility of research in general means research participants are actively engaged in the research process, patients seek out research participation, and research participants help researchers design research in ways that were unheard of in the early 1990s.

The new Common Rule

In 2017, the first revision to Common Rule in over twenty-five years was published, taking steps to provide a better balance between protection of human subjects and facilitation of new research advances. (Table 3). The revisions strive to reduce some of the administrative burden on researchers and to reduce delay and ambiguity in the current IRB process.

Under the new Common Rule, more research will be considered minimal risk, and even more research will have the opportunity to be exempted from the regulations. In addition, the renewal requirements for minimal risk research have been removed from the Common Rule, reducing administrative burden on IRBs and researchers. New requirements for informed consent will require new informed consent templates and revisions to the informed consent process. The requirement for single IRB review for multi-center studies by 2020 will result in more collaboration with external IRBs.

The effective date of the revised common rule was January 19, 2019.

Conclusion

As a national research community, we now find ourselves in a new era of research. The revision to the Common Rule is just one more example of how the research world is changing. Navigating change can be difficult and complicated; however, the changes provided by the revised Common Rule will offer advantages to researchers and IRBs while providing better protection for human subjects. For the first time since 1991, the research community has an opportunity to build a more desirable research environment, necessitating flexibility and better communication between IRBs and researchers alike. Taking advantage of this new era will require strong collaboration between IRB administrators, research coordinators, and researchers to find and utilize those areas of flexibility within the regulations.

TABLE 1

How Context Drove the Regulations

- Tuskegee syphilis studies:

- Coercion

- Lack of understanding

- Failure to treat

- Harm

- Unverified results

- Belmont Report:

- Respect for persons

- Beneficence

- Justice

- Common Rule:

- Minimization of risk

- Risk/benefit ratio

- Informed consent

- Protection of vulnerable populations

TABLE 2

The Revised Common Rule

- Balance protection of human subjects with facilitation of research

- Reduce administrative burden, delay, and ambiguity

- Address protections across a broader variety of research

- Harmonize human subjects policies across federal departments and agencies

- New exempt categories based on risk profile

- New requirements for the informed consent process

- “Broad consent” as a new form of informed consent

- Use of a single IRB for multi-site projects

- No continuing review of minimal risk research

Thank you for posting this very interesting summary. These changes are still new to many of us and we should all work to adapt them into our common practice while getting site up and running.

Human anatomy is an old scientific field, dating back to the third century, as is well known. Since then, there have been several developments and changes in human medical research that have brought us to where we are now. Central BioHub integrate dynamic data-driven digital technologies into biospecimen distribution. To buy high-quality human biospecimens for your research we therefore built the most dependable click-and-buy online channel by eliminating all the flaws in traditional study sample procurement. Every order is immediately processed and swiftly delivered to your location at Central BioHub. Additionally, select CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS, ICD-10-CM CODES, and LABORATORY PARAMETERS to learn more about advanced search possibilities.

https://centralbiohub.de/blogs/human-biospecimens

Access to human samples from patients is crucial for advancing diagnostic and clinical research globally. These specimens are highly valuable for molecular and laboratory research, leading to the development of cutting-edge diagnostic tools. To support in-vitro diagnostic, clinical trial, and clinical research, Central BioHub offers a broad selection of human biosamples in different matrices, including serum, plasma, urine, PBMC, CSF, and more. Explore our collection to find the perfect human specimens for your research needs.

https://centralbiohub.de/biospecimens/specimen-matrix

Are there any changes in the definition of the “Human Subjects” in the last ten years? Does anyone know that?