Adam Donat, MS, Martin Hamilton, MSN-FNP, Irfan Khan, MS, Nichole Chamberlain, MSN-FNP

Organization: Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Office of Compliance, Division of Bioresearch Monitoring

The findings and conclusions in this article should not be construed to represent any Agency determination or policy.

Technology continues to permeate every facet of the modernized world. As the medical field relies more and more on computerized technology, unique issues have emerged especially in the area of clinical trials and the use of Electronic Data Capture (EDC). Novel approaches to safeguard data integrity and human subjects need to be considered at every juncture of the research process.

The significance of EDC is illustrated through national funding initiatives. In 2009, President Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), which provided expenditures in response to the economic crisis. One of the goals is for the federal government to appropriate funds to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for computerization of patients’ health records. ARRA authorized CMS expenditures to implement incentive payments to health providers and institutions for the meaningful use of certified electronic health records (EHR) technology (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2012). It is estimated that 20% of doctors and 10% of hospitals currently use EHRs and these numbers are climbing (Kaiser Family foundation, 2011). The adaptation of electronic medical records in clinical trials allows researchers to easily and efficiently share pertinent health information about subjects with the subjects’ primary care providers (PCPs).

In clinical trials, EHR and EDC are widely utilized tools to keep track of subject outcomes and research requirements such as lab reports, progress notes, adverse events reporting, and randomization of subjects. These tools allow industry to efficiently share subjects’ case history records between PCPs, study sponsors, clinical investigators, and data management units. This provides real-time analyses and review of clinical trials data, reporting of real-time adverse events and serious adverse events, shortening the overall study duration, and having the potential to save expenses of conducting multiple clinical trials. Furthermore, it allows multiple methods for collecting clinical trial data electronically rather than traditional paper-based case report forms (CRFs). These methods include personal computers (PCs), tablets, smartphones, and personal digital assistants (PDAs)

It is essential that the data quality and integrity of clinical trials maintain high standards as industry moves forward with the use of EDC. This article provides multiple scenarios to show the importance of establishing a robust data management plan when using EDC for collecting clinical trial data. The best practices to consider safeguarding against regulatory pitfalls introduced with the increased use of EDC in clinical trials will be discussed.

EDC Case Examples

Case 1: Electronic Data Transcription Error

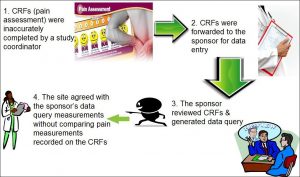

Background: A clinical trial included a pain assessment as part of the evaluation of an investigational device. As illustrated in figure 1, the pain assessment utilized facial expressions coinciding with a numerical value to quantify the level of pain. Site staff asked subjects to provide a numerical value for pain to be recorded on case report forms (CRFs) and the staff casually drew a line on the pain scale that did not always coincide closely with the numeric score from the subject. Study staff then sent the CRFs to the sponsor for data entry and data analyses. The electronic data entry system used the lines drawn on the CRFs instead of the numerical value for data entry and generated a different numeric pain value. The sponsor sent the discrepant data query to the site for review and the site staff concurred with the sponsor’s numerical pain value without auditing the source data to ensure accuracy. This resulted in the sponsor providing incorrect data to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in support of a premarket approval application.

Figure 1: Electronic Data Transcription Error

Figure 1: Electronic Data Transcription Error

Assessment: In review of the evidence, the FDA found that the sponsor did not adequately train or instruct site staff how to accurately fill out the CRFs from source documentation. In addition, the poor design of the electronic data entry system resulted in data discrepancy. A vague data management plan coupled with a poor electronic data entry and CRF design complicated this issue.

Considerations/Best Practices: This case sheds light on the importance of establishing a robust data management plan including electronic data entry, and providing adequate training to study staff as to their roles and responsibilities during the course of the study. This includes providing detailed and hands-on instruction as to the correct process to complete study documents. As elucidated in this example, a simple mistake can have deleterious consequences.

Another consideration is to create a detailed study protocol to include a comprehensive data management plan and instructions on completing study documentation. Having a detailed monitoring plan also provides safeguards to ensure data is accurate. Ultimately, the responsibility for the conduct of any FDA regulated study resides with the principal investigator, regardless of which study staff made the error or what the delegation of authority was.

Case 2: Data Manipulation of Commercial Software

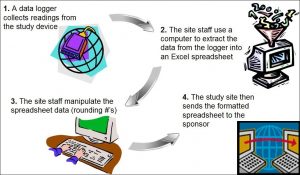

Background: A clinical trial used a data logger to collect readings from a study device. Site staff used a computer to extract the information from the data logger into an Excel spreadsheet. The site staff manipulated data on the spreadsheet rounding the numbers. The sponsor used the manipulated data sent from the site.

Figure 2: Data Manipulation of Commercial Software

Figure 2: Data Manipulation of Commercial Software

Assessment: The site did not preserve the original source documentation from the data logger as site staff manipulated the data forwarded to the sponsor. This scenario relates to other cases where study staff alter information in source documents or inaccurately transfer data to CRFs. The site sends the incorrect data to the sponsor who forwards the information to the FDA in support of an application. The discrepant information is found during an FDA inspection, the site is then penalized for the errors and ultimately, the device application is in jeopardy of disapproval.

Considerations/Best Practices: The site should perform routine audits of study documentation to verify the accuracy of the data recorded. The site should also implement security measures to ensure the integrity of electronic source documentation. As per Part 11, electronic records should have limited access and password protection. All modified electronic data should not obscure the original data and should reflect the date, time, and person responsible for the changes. Additional considerations to safeguard the integrity of data include devising study protocols to include a detailed description of electronic security measures employed to protect data integrity and to include a robust monitoring plan. Sponsors should ensure that the site staff is adequately trained to use the electronic systems in compliance with the study requirements and monitor accuracy of data handling at the site.

Case 3: Scanning Discrepancy

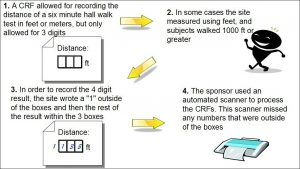

Background: A study utilized a six-minute walk to record the distance walked by subjects following the implantation of a device. The CRF allowed site staff to record the distance walked in feet or meters. The CRF contained enough room to record up to three digits of the distance walked since the formatted boxes provided allowed for only one digit per box. In instances where subjects walked a distance requiring four digits, site staff wrote the first digit outside of the first box and the rest of the numbers recorded within the boxes. The site sent the CRFs to the sponsor where staff scanned them into an electronic format.

Figure 3: Scanning Discrepancy

Figure 3: Scanning Discrepancy

Assessment: The computerized system did not record any of the numbers written outside the boxes, which were those recorded in feet. The monitor did not catch this error, as few subjects walked greater than 1000 feet.

Considerations/ Best Practices: In addition to the considerations articulated in Case 1 above, site staff should have been trained to recognize that writing the number outside of the box could cause a problem. The sponsor should provide an easy way for sites to report these issues as they are discovered.

Case 4: Electronic Data Entry Errors and Remote Monitoring

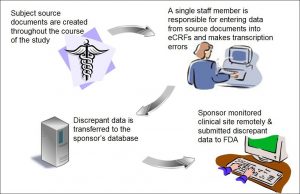

Background: A site utilized electronic case report forms (eCRFs) to submit its data to the sponsor and the sponsor conducted its monitoring remotely. One individual from the site was responsible for retrieving study data from subjects’ source records and for entry of the study data indices to eCRFs. The individual capturing the data on the eCRF sent many erroneous data to the sponsor.

Figure 4: Electronic Data Entry Errors and Remote Monitoring

Figure 4: Electronic Data Entry Errors and Remote Monitoring

Assessment: As a result of the single person data entry, the site had many discrepant data between the subjects’ eCRFs and source documents. Because the sponsor did not devise a robust system to ensure that the site accurately captured its data, the sponsor received and utilized erroneous data to assess the efficacy of its device. Moreover, the sponsor had no way of verifying that the site entered the data onto the eCRF correctly because it monitored the site remotely.

Considerations/ Best Practices: Clinical sites should designate a minimum of 2 research staff member to perform electronic data entry to mitigate errors. When sites use eCRFs for data entry, the sponsor should consider onsite monitoring to verify the accuracy and completeness of the data entered onto the eCRFs. If remote monitoring is preferred, the sponsor should consider the following steps: Firstly, devise a plan to ensure sites capture subjects’ data on paper CRFs. Secondly, request that research staff at participating centers transcribe subjects’ data from the subjects’ source records to their corresponding paper CRFs and from the paper CRFs to eCRFs. Thirdly, request that the research staff send copies of the paper CRFs to an individual at the sponsor’s site and/or at the data management center who thereafter, performs audits of the eCRFs to ensure data is entered onto the subjects’ eCRFs accurately and completely. The auditor would complete this task by comparing the paper CRFs to the eCRFs.

Discussion/Conclusion

As the use of EDC in clinical studies increases, it is becoming clear that such systems present new challenges in ensuring data integrity and subject safety. Based on the cases discussed above, several best practices are useful across a variety of situations. During the study-planning phase for example, designing staff training on the study’s data management procedures helps to ensure each site is collecting accurate data uniformly across the study. In addition, outlining data management procedures in a data management plan prior to study initiation provides a structured approach that protects data integrity and a documented source for reference throughout the course of the study.

Although data management plans are not required by regulation, their use is becoming increasingly common and the recently revised International Organization for Standardization [ISO] 14155:2011 “Clinical investigation of medical devices for human subjects – Good clinical practice” includes a section dedicated to these procedures in its Clinical Investigational Plan outline [Annex A, Section A.8] (ISO, 2011).

It is also important during the study-planning phase to consider the design of an EDC system and its use throughout the course of the study. For example, the EDC system should incorporate security measures to limit access to authorized personnel only. The system should also utilize an audit trail to document changes to data. When these changes occur, the system should record the date, time, and person responsible for the change. Furthermore, the original data should be preserved to allow an auditor to view what was changed. A good resource on the considerations when implementing electronic data systems in clinical studies is the FDA guidance document titled “Computerized Systems Used in Clinical Investigations (FDA, 2007).”

Once a study is underway, a continued effort is necessary to ensure study staff is using the EDC system appropriately. Thorough study monitoring by the sponsor is essential in ensuring the accuracy and completeness of data entered into the eCRFs. Furthermore, clinical sites should implement their own quality control measures to help mitigate errors. Study sponsors should provide ongoing training for study staff on the use of EDC systems to address evolving situations such as staff turnover or system updates that change the procedures for use. Finally, throughout the course of the study, sponsors should ensure an open line of communication between themselves and the study sites to quickly identify and correct difficulties in using the EDC system. Additional information on FDA’s current thinking related to the requirements of 21 CFR Part 11 in clinical studies can be found in the guidance document titled “Part 11, Electronic Records; Electronic Signatures — Scope and Application (FDA, 2003).”

EDC allows for greater efficiency and accuracy in running clinical studies when compared to traditional paper-based methods and therefore, firms are increasingly adopting these systems. However, EDC introduces unique challenges that did not exist with the paper-based methods. This article outlined some electronic data issues based on real-world cases and outlined the best practices that, if appropriately implemented, could help prevent them.

A simple oversight with an EDC system can cause significant problems over the course of a clinical study. Therefore, it is essential to thoroughly plan and monitor the use of EDC systems. By paying the necessary attention to electronic data issues such as these, clinical study professionals can help to ensure a productive and safe clinical study.

FDA recognizes the importance of providing transparency to clinical study professionals related to EDC issues. In order to bring clarity to EDC regulatory expectations, FDA continues to work diligently with industry to update guidance documents. Stay tuned for the release of updated guidance documents.

References

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2012). EHR incentive programs. Retrieved June 13, 2012, from http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html?redirect=/EHRIncentivePrograms

Food and Drug Administration. (2007). Guidance for Industry: Computerized Systems Used in Clinical Investigations. Retrieved August 15, 2012, from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM070266.pdf

Food and Drug Administration. (2003). Guidance for Industry: Part 11 Electronic Records, Electronic Signatures — Scope and Application. Retrieved August 15, 2012, from http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/ Guidances/UCM126953.pdf

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. (2011). Health Information technology. Retrieved June 11, 2012, from http://www.kaiseredu.org/Issue-Modules/Health-Information-Technology/Background-Brief.aspx

International Organization for Standardization. (2011). ISO 14155:2011 – Clinical investigation of medical devices for human subjects — Good clinical practice.

Integrity has become one of the main issues with everything being digitalized now. But then, if done correctly, data through digitalization can be made more secure than the data from paper-based work. Depends on how much effort people decide to put in. Great article. Love the scenarios. Great work!

Exciting prospects ahead with EDC systems in clinical trials! Real-time data, improved efficiency, and patient-centric approaches will shape the future.

The future of clinical trials using Electronic Data Capture (EDC) systems is thrilling. These systems act like super organizers for trial data, making processes smoother and more reliable.

The coolest part? EDC can team up with wearables and apps to gather even more information from participants, bringing trials into the digital age. Despite hurdles like security, EDC systems are leading to faster, more efficient, and more exciting clinical trials.